I found some interesting graphs by Japan's Ministry of Finance describing the Current Japanese Fiscal Condition .

Japan's national debt as a % of GDP

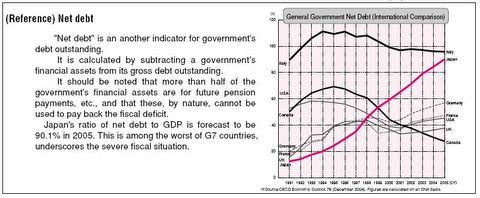

Japan's net national debt

The above graphs were produced by Japan's Ministry of Finance.

The most current report I could find in English was from September 2005.

Japan's National Debt Hits New High

Japan's government debt ballooned to a record high of JPY 795.8 trillion (USD 7 trillion) at the end of June, according to a report released by the Japanese Finance Ministry. It was projected to be JPY 774 trillion for this fiscal year, so the national debt is growing faster than expected.Even though Japan has a positive balance of trade with the US, Japan's government is squandering it. Basically, the private sector is saving and the government takes those savings and wastes them in imaginative ways.

Japan has relied on government bond issues to make up for falling tax revenues. This has turned the nation into one of the world's most indebted countries. Japan 's public debt burden is now almost 160 per cent of its GDP, which makes it the highest in the industrialized world.

On February 15th 2006 Japan's Fiscal Policy Minister said Japan May Have to Cut Spending by 20 Trillion Yen

The Japanese government may have to cut total spending by 20 trillion yen ($171 billion) by April 1, 2011, to meet its goal of balancing the budget if it does not raise taxes, Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Kaoru Yosano said.Given that it is already over 160% by earlier MOF projections I am not sure where the 151% comes from. Nonetheless, it should be quite clear by any means that the idea of Japan being a "nation of savers", as least as far as government deficit spending goes should be shattered.

The projection was submitted at today's meeting of a government economic panel in Tokyo. Yosano made the comments following the panel's meeting.

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi has set a goal of balancing spending and revenue, without depending on new bond sales, by the early next decade. Japan can't stop the expansion of its public debt by spending cuts alone, Koizumi told parliament on Feb. 7, signaling Japan may have to raise taxes after he steps down in September.

Japan's public debt, combining that of both national and local governments, will reach 151 percent of gross domestic product by March 2007, the Ministry of Finance projected in December.

What about that trade surplus?

On February 22nd Forbes reported Japan posts first trade deficit in 5 years, the largest since 1983.

Japan posted its first trade deficit in five years in January as surging crude oil prices bloated imports but economists believe that the trade gap was a one-off event.Let's explore the idea that "surging crude oil prices" are to blame.

The Ministry of Finance said the trade balance plunged into a deficit of 348.9 bln yen last month, against a surplus of 193.9 bln yen a year earlier, also due to a long New Year holiday at the start of the year.

'Due to a long New Year break, exports normally drop in January compared to other months, while surging crude oil prices and the cold weather helped imports stay at high levels, thereby resulting in the first trade deficit in five years,' an MoF official told a news briefing.

'Looking back at our records in the past 20 years, it was only in January that Japan has posted a trade deficit,' he added.

The last time Japan reported a trade deficit was in January 2001. The latest trade gap was the largest since January 1983 when the deficit reached 409.8 bln yen but nowhere near the deficit of 824.8 bln yen posted in January 1980.

Last month's figure was much wider than market expectations. Economists on average projected a deficit of 101.9 bln yen, according to a Nihon Keizai Shimbun poll of 23 research institutes. The forecasts ranged from a deficit of 378.6 bln yen to a surplus of 158.0 bln yen.

But the finance ministry said the trade deficit may be a blip and expects exports to remain brisk.

Given that crude prices ran up from $25 to $70 without causing a deficit and stayed in a range near $62 (8 dollars off the high) for about 6 months, can oil really be the culprit?

Let's see if the YEN has any clues.

Hmmm. Does that help answer the question?

Of course, Japanese exports should have been helped by been helped by a falling YEN. Were they? I suspect that a slowing world economy may be hurting exports everywhere. What we do know for sure is that the falling YEN did not help Japan at all on its oil purchases.

Bloomberg is writing Japan's Boom May Explode Yen-Carry Trade.

Surprisingly strong growth in Japan is raising many eyebrows, not least those at the central bank anxious to scrap its zero-interest policy.Although the Japanese carry trade has a history of blowing up in spectacular fashion, it now seems that all eyes are on it. That makes the carry trade far less likely to be any sort of economic trigger. The last time the Yen carry trade did blow up, nobody talked about it beforehand. A watched pot never boils. In 2000 Greenspan was worried the economy was too strong (it imploded). In 2001 the FED and Bernanke were worried about deflation (the economy roared when interest rates were slashed to 1%), now the FED is worried about inflation again while Japan is still worried about deflation.

There can be little doubt 5.5 percent growth between October and December pushed the Bank of Japan further in that direction. Oddly, there are few if any signs global markets are bracing for higher debt yields in Japan.

Why? Japanese rates have been negligible for so long that investors take them for granted. This, after all, is the economy that's cried wolf too many times. The reason investors from New York to Singapore aren't ecstatic about Japan's recovery is the sense we've been here before -- many times.

Yet Japan's latest growth figures should make believers of some of the biggest skeptics. Not only did exports boost the economy in the fourth quarter, so did personal spending -- a sign optimism is spreading to households around the nation.

Rest assured the BOJ is noticing and will soon begin pulling liquidity out of Asia's biggest economy. Once that process begins, there's no telling how aggressive the BOJ will be and what effect it will have on bond yields.

Where Liquidity Begins

There are two reasons Japan's rate outlook is a huge story for global markets. One, yields in the biggest government debt market will head steadily higher for the first time in more than a decade. Two, it may mean the end of the so-called yen-carry trade.

"All liquidity starts in Japan, the world's largest creditor country," said Jesper Koll, chief economist for Japan at Merrill Lynch & Co. "When rates go up here, rates go up everywhere."

What makes the carry trade so worrisome is that nobody really knows how big it is. For example, the BOJ has no credible intelligence on how many hedge funds, investors and companies have borrowed cheaply in ultra-low-interest-rate yen and re-invested the funds in higher-yielding assets elsewhere.

A popular form of the strategy exploits the gap between U.S. and Japanese yields. Anyone borrowing for next to nothing in yen and parking the funds in U.S. Treasuries received a twofold payoff: the 3-plus percentage-point yield difference and the dollar's rise versus the yen. The latter dynamic boosts profits by the time they're converted back to yen.

Yet as the BOJ raises rates and more investors buy into Japan's revival, the yen is sure to rise, much to the chagrin of carry-trade aficionados. Realization the trade is moving against investors may send shockwaves through global markets.

It would start slowly with speculators suddenly closing positions that are becoming more expensive: dumping Treasuries, gold, Shanghai real estate, shares in Google Inc. or whatever else they used yen borrowings to bet on. The chain reaction would accelerate once the mainstream media jumped on the story.

If all this sounds far-fetched, think back to late 1998, which offers an example of the damage a panic among carry-traders can do.

Remember 1998

In October of that year, Russia's debt default and the implosion of Long-Term Capital Management LP shoulder-checked global markets. The disorienting period culminated in the yen, which had been weakening for years, surging 20 percent in less than two months.

Suddenly, just about anyone who'd borrowed cheaply in yen rushed for the exits. It prompted frantic conference calls among officials in Washington, Tokyo and Frankfurt. Just how big was the yen-carry trade? How much leverage was involved? What could policy makers do, if anything, to regain control?

Japan is arguably in its own state of Economic Zugzwang and very reluctant to make a move. On one hand, Japan has a desire to get off its ZIRP policy (which would tend to strengthen the YEN if they do) on the other hand Japan still has an overwhelming desire to maintain exports in a world economy that is clearly slowing. Compounding the problem is rising oil prices as the YEN weakens vs. a declining value of its massive US Treasury portfolio if the YEN would strengthen. Eventually the market is going to force Japan to do something. In the meantime this article should be a reminder that every major fiat currency has huge structural flaws lurking somewhere. One can only choose be between relative degrees of fiscal insanity. That unfortunately is the current sad state of affairs.

Mike Shedlock / Mish

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment